JesseKane

Yamadori

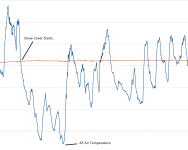

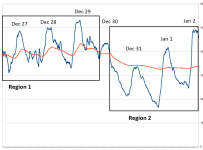

This is the second winter of my bonsai fascination and the first year I'm over-wintering outside. I built a small frame buried about 10 inches into the ground in a sheltered portion of my yard, and being an engineer, I had to instrument the trees with some temperature monitors! We had a cold night recently with a low of 16deg F air temp. As the air temp was falling, I was watching the soil temp fall as well, albeit much slower. But when the soil got to 32deg F, it stopped falling! Checking the data today, I saw that the soil temp more or less flattened for the three days that we've had nightly temps drop into the teens or low 20's. Here is a plot of the data, the blue line is air temp about 18inches above the ground and the orange line is soil temp of a JM in a gallon nursery container, with the temperature in degrees F on the right axis.

I've marked two areas of interest in the plot.

Region 1:

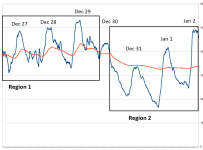

This shows daily temperatures from December 27th to early morning December 30th. You can see that the soil temperature tracks air temperature pretty closely, but with the peaks smoothed out. This is the insulative effect of the mulch around the pots in effect. Insulation doesn't necessarily keep things warm, what it does is reduce the heat flux in and out of what is insulated. The result in this case is that the soil temperature changes slower than the air temperature, effectively reducing the extremes on both the hot and cold side.

Region 2:

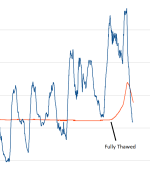

This is a much more interesting series of days. You can see that the effect of the insulation during the night of the 30th, with soil temp dropping but at a much slower rate than the air temp. But as the soil temp nears 32 degrees, suddenly it stops dropping nearly as fast. If the only effect was insulation, I would expect the temp to continue to drop and to see it increase very quickly once the air temp rose above the soil temp on January 1st. Heating from the ground is also surely contributing as well, but the sudden flattening of soil temp slope at exactly the freezing point of water points me into a different direction. My theory is that the main contributing factor is the latent heat of fusion of the water in the soil.

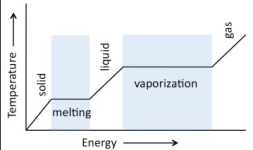

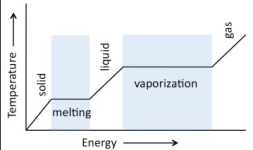

Water has an amazing effect where it releases a large amount of energy in the form of heat when it experiences phase changes, such as steam condensing into liquid water or water freezing into ice. For the three days shown here, the water content of the soil is in the slow process of freezing and thawing without every becoming fully frozen or thawed. Here's a picture describing the latent heat effect in water. This is the same mechanism that allows trees to cool their foliage on hot days through transpiration of water and it's evaporation.

Other than just being a cool physical phenomenon that I noticed while nerding out about my weather station data, this also shows the importance of making sure your trees don't dry out during the winter. Dry soil will not have the same phase change buffering effect that water can provide and will be much more prone to sudden drops far below freezing.

Ok rambling done, thanks for attending my lecture! I'll be sure to post more weird things I notice over the winter. Especially hoping to see the soil temp continue to drop after being fully frozen and reflect the trend of the latent heat diagram when it inevitably gets sub-zero this winter.

I've marked two areas of interest in the plot.

Region 1:

This shows daily temperatures from December 27th to early morning December 30th. You can see that the soil temperature tracks air temperature pretty closely, but with the peaks smoothed out. This is the insulative effect of the mulch around the pots in effect. Insulation doesn't necessarily keep things warm, what it does is reduce the heat flux in and out of what is insulated. The result in this case is that the soil temperature changes slower than the air temperature, effectively reducing the extremes on both the hot and cold side.

Region 2:

This is a much more interesting series of days. You can see that the effect of the insulation during the night of the 30th, with soil temp dropping but at a much slower rate than the air temp. But as the soil temp nears 32 degrees, suddenly it stops dropping nearly as fast. If the only effect was insulation, I would expect the temp to continue to drop and to see it increase very quickly once the air temp rose above the soil temp on January 1st. Heating from the ground is also surely contributing as well, but the sudden flattening of soil temp slope at exactly the freezing point of water points me into a different direction. My theory is that the main contributing factor is the latent heat of fusion of the water in the soil.

Water has an amazing effect where it releases a large amount of energy in the form of heat when it experiences phase changes, such as steam condensing into liquid water or water freezing into ice. For the three days shown here, the water content of the soil is in the slow process of freezing and thawing without every becoming fully frozen or thawed. Here's a picture describing the latent heat effect in water. This is the same mechanism that allows trees to cool their foliage on hot days through transpiration of water and it's evaporation.

Other than just being a cool physical phenomenon that I noticed while nerding out about my weather station data, this also shows the importance of making sure your trees don't dry out during the winter. Dry soil will not have the same phase change buffering effect that water can provide and will be much more prone to sudden drops far below freezing.

Ok rambling done, thanks for attending my lecture! I'll be sure to post more weird things I notice over the winter. Especially hoping to see the soil temp continue to drop after being fully frozen and reflect the trend of the latent heat diagram when it inevitably gets sub-zero this winter.